Coatino will help users research and adjust ingredients directly in the laboratory.

Coatino will help users research and adjust ingredients directly in the laboratory.

Bearing names such as Siri and Alexa, virtual assistants are now a part of many families around the world helping in their daily lives. Whereas they were found in only one per cent of US households in 2016, this figure had risen to 20 per cent just two years later.

If everything goes according to Dr Gaetano Blanda’s wishes, this will only be the beginning. Blanda wants to turn voice-controlled digital assistants from simple helpers for daily life into chemistry experts and use them in a place where a comprehensive amount of specialised knowledge is needed and a technical language is spoken: the laboratory.

As the head of the Coating Additives Business Line at Evonik, Dr Blanda knows about the great demands that the new lab assistants have to fulfil with regard to scientific expertise and language skills. His team specialises in formulations for the coatings industry and the associated additives.

|

|

Coatino ... a digital assitant for the coatings sector. |

In order to exactly meet the customers’ wishes with respect to colour, gloss, and durability, the experts have to create complex mixtures in the lab which they supplement with the right additives. Thousands of combinations are possible – far more, in fact, than the human brain can handle.

The experts spend correspondingly much time searching through notes and data sheets on their desks. So a digital assistant – Coatino – will now help users research and adjust ingredients directly in the laboratory.

The idea for Coatino was born during a strategy meeting at Coating Additives. “We talked about new ways in which business could develop,” says Dr Oliver Kröhl, head of the strategic business area development at Coating Additives and the project’s manager. “Innovations are no longer just limited to finished products or processes. Instead, you need to demonstrate your ability to come up with solutions in the form of new services and business models.”

The researchers focused on everyday challenges for the formulation of coatings and paints and soon decided that they could use a voice-controlled digital formulation assistant. The team was thrilled by the idea. But is this what the experts in the lab actually need?

To find this out, the scientists coated an empty can of paint in the company’s colours. They then put it into the laboratory, where they filmed a discussion between a colleague and the can. In the video, the user asked the can about a suitable waterborne anti-foaming agent for a wood coating. The can gave its reply, provided the lab employee with a selection of products, and ordered a sample.

|

|

In meet the customers’ requirements with respect to colour, gloss, and durability, complex mixtures are created in a laboratory. |

“Back then, the questions were answered by a colleague who stood behind a wall,” says Kröhl. “Although this was rather ad hoc, we wanted to tangibly test our idea with customers and quickly get feedback.”

The idea attracted a great amount of interest. This approval encouraged the developers to move into uncharted territory. “We’re experts for paints and coatings, but not for voice-controlled assistants,” says Kröhl.

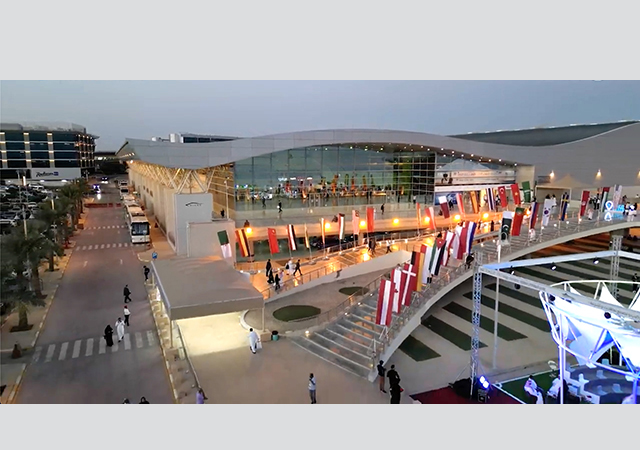

They aimed to develop a prototype assistant in time for the European Coating Show (ECS) last year.

This was no easy task, because conventional voice-recognition systems were unable to handle the specialist vocabulary. “The usual assistants simply can’t understand our language,” says Kröhl. They quickly reach their limits when you ask them about dispersion, rheology or silicone resins, for example, and they can, at best, only supply general information.”

The high-throughput experimentation unit for the testing of coating recipes at the Coating Additives Business Line provides an important pool of data for the coating industry’s digital assistant. This unit, which is housed at Evonik’s Goldschmidtstrasse location in Essen, doses raw materials, formulates them to create coatings, and characterises the finished coatings. All of this runs fully automatically according to a precisely defined programme that can be reproduced at any time. As a result, the unit can formulate an average of 120 samples in 24 hours. The results can be called up and reproduced at any time. If this data is linked with Coatino, customers will receive daily updated data about individual coating formulations.

Virtual assistants have to be able to do a lot more in order to formulate a coating, says Kröhl. “If they don’t know the components’ properties and how they interact, they won’t be any help in the laboratory,” he points out.

Paints, lacquers, and other coatings basically consist of four components: solvents, binders, pigments, and additives. A solvent keeps a wall paint in a liquid state and evaporates after the paint is applied, causing it to dry. Pigments give the paint the desired colour. Binders, which are colourless, are used to ensure the paint remains attached to the substrate. Additives, which make up less than five per cent of a formulation, eliminate foam when paint is applied. They also prevent the paint’s pigments from agglutinating. They make coatings thixotropic, that is, they make them easy to apply, but prevent them from forming runs when they dry on vertical surfaces. Other additives make coatings more scratch-resistant, for example.

Even if only 10 curing agents, 10 binders, 10 pigments, and 10 additives are considered during the development of a coating recipe, these numbers translate into 10,000 possible combinations. And this doesn’t even take into account variations in the ratios of the components used.

“Customers have very precise ideas about the capabilities that a product should have once it’s finished,” says Blanda.

In order to develop a functional voice-controlled assistant for the coatings industry, the researchers at first began to structure all of the available information and feed it into a huge database. In the next step, they made it possible to call up this information using a voice-control function.

Coatino had to learn that “additive” designates a certain category of coating components. In the next step, the assistant has to access its data, search through it, create suitable links, and assign the data to a possibly relevant result. To do so, it first breaks down the sequence of sounds into their smallest components and conducts a data search on the basis of characteristic properties. The researchers also want to make sure that the speaker’s dialect or accent won’t hamper the result. The ultimate aim is to enable Coatino to understand customers’ pronunciations worldwide. Added to these challenges are the speakers’ different talking speeds and pitches as well as the specific context of a discussion.

“The training process is very nerve-wracking,” says Kröhl. “And after the trial run with our colleague in Shanghai was finally successful, it went wrong with our colleagues in Essen.”

For almost two years now, Coatino has been jointly developed and trained by the business line and an external development company from Berlin. The assistant passed its first important development test when the prototype was demonstrated at the ECS.

Coatino can say a lot of things. When asked about suitable additives, it not only presents a list of products but also prioritises them. “Coatino can tell me which additive would be best suited for my formulation and my requirements. It can thus give me well-founded recommendations,” says Blanda.

Once a user has found the desired product, he can issue a voice command to tell Coatino to order a sample, directly call up the pertinent technical data sheet by e-mail or have a conversation with an expert arranged. “For us, customer-oriented digital solutions enable people to talk with one another more efficiently about innovative solutions,” says Kröhl.

The Coatino prototype was ready just in time for the start of the European Coating Show. “The feedback was even better than we’d hoped. We were able to gain some of the customers as first users who will test the assistant,” he says.

They will pass on their experiences to Blanda and his team. “We wanted to get the customers involved at an early stage,” says Blanda. “Such a project can only work if customers also think it benefits them.”

In 2020, the researchers plan to make Coatino available for the entire coatings industry.

However, there is no end in sight for the system’s further development. “When you use digital assistants, you continually come up with ideas for new features,” says Kröhl.

For example, Coatino could conceivably not only supply existing formulations but also suggest its own new mixtures. The scientists could directly test these mixtures in the lab and enhance them for their own use.

“Our Coatino might one day really become an artificially intelligent entity,” says Blanda. “But we still have a long, long way to go until then.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

Doka (2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)